The Unseen Impacts of Trauma on Employees and the Workplace

.jpg?width=2120&name=GettyImages-607477467%20(1).jpg)

Over two years ago, the Covid-19 pandemic upended life as many people know it. Recent changes have included new health precautions, mask mandates, and supply chain shortages. Along with changes to day-to-day life, Covid-19 caused widespread illness and many deaths. What’s especially challenging is that almost everyone has been expected to live life and work as normal during a time when life feels anything but normal.

Given the circumstances during the past two years, it is not surprising that many employees have experienced recent trauma. Perhaps even less surprising is the lack of conversation about the collective trauma many have faced in the past 2 years. According to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, trauma occurs when an individual experiences lasting negative effects on their overall well-being in response to one or more events that are physically harmful, emotionally harmful, or life-threatening.

Mental health has traditionally been a taboo topic, particularly in the workplace. Many organizations and leaders either fail to acknowledge employees’ traumatic experiences and mental health needs or do so minimally. This lack of discussion has led to employees feeling unsupported when facing these issues (Moll, 2014). In addition, the lack of conversation on trauma and employee mental health also results in a black box of untapped knowledge regarding the impact of trauma on work performance and work life.

To better understand the prevalence and effects of trauma on workers worldwide, employees across the globe responded to a survey about traumatic experiences over the last two years

Prevalence of Trauma

Given recent and current events, it is expected that many people have faced trauma recently. However, there has been a limited acknowledgment of the prevalence of collective trauma as well as its impacts on individuals, workplaces, and communities.

In the past two years, since the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic, employee mental health conditions have reached crisis levels. In fact, one study of over 1200 Chinese respondents found that 54% rated the impact of the pandemic on their mental health as ‘moderate’ or ‘severe” (Wang, and colleagues, 2020). Research is currently limited on the extent of the mental health impact of Covid-19; however, anecdotal evidence and early indicators from studies of healthcare workers reveal increased psychological pressure, trauma, and mental illness (Vizheh, and colleagues, 2020).

Besides the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic, trauma may be more prevalent in certain occupations and populations. In terms of occupations, trauma is most prevalent in health care workers, police officers, disaster relief workers, firefighters, and employees who experienced a traumatic event in the workplace such as a building collapse or robbery (Lee et al., 2020). In a meta-analysis by Lee and colleagues, the researchers examined the incidence of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and found ranges of 2.6% fitting PTSD criteria 14 months after an earthquake cleanup to 53.3% in a group of workers who previously experienced PTSD symptoms while working recovery and clean-up after the September 11th attacks in the United States of America. There are also disparities in terms of race and trauma experienced. Research by Roberts and colleagues (2010) found that Black respondents reported the highest levels of trauma and White respondents and Hispanic respondents reported intermediate levels of trauma and Asian respondents reported the lowest levels of trauma. According to research by Kira and colleagues (2021) the Covid-19 crisis increased disparities because groups of people who already face racial inequities also experienced increased exposure to Covid-19 infection and death in their communities.

Survey Description

Full-time workers were recruited through an online participant pool in which members complete surveys in exchange for monetary incentives. All 513 respondents in this survey completed their participation in February 2022. Out of the 513 respondents, 65.9% (338) reported they were women, 31.6% (162) reported they were men and 2.5% (13) reported they were nonbinary or other. According to survey respondents, 10.1% (52) were Asian or Pacific Islander, 11.4% (58) were Black or African, 4.0% (24) were Hispanic or Latino, 3.9% (20) were Multiracial, 4.5% (25) were Native American, 62.6% (321) were White or Caucasian, and 2.5% (13) reported “Other”. Survey respondents ranged in age from 19 to 77 with a mean age of 44. The majority of the survey respondents were from the United States 63.8% (329) and the second-largest country represented in the sample was United Kingdom 21.3% (110). Remaining countries included much smaller samples from Poland 5.8% (30), South Africa 5.0% (26), Canada 2.7% (14), New Zealand 1.0% (5), Australia .2% (1) and Japan .2 (1).

Traumatic experiences are typically thought of as assaults and car accidents; however, there are many experiences that are traumatic. Many people do not recognize their experiences as traumatic, so instead of using the word “trauma,” employees responded to the survey by reading the following question, which used the definition of trauma to ask if they had experienced such an event: “During the past 2 years, have you experienced an event that negatively affected your well-being for a month or more?”. Respondents answered using the following options: ‘Yes’, ‘No’, ‘Prefer not to Respond’. Two years was selected as the time period for the study so that we could focus on experiences that occurred during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Next, respondents who answered “yes” to the previous question were asked “Was this event work-related?” The last question on the traumatic event asked “If you are comfortable doing so, please briefly describe the nature of the negative event. If you prefer not to answer, type "skip."” These questions were part of a larger survey administered quarterly to working adults around the world. Questions about well-being, stress, sleep, working relationships, and intentions to quit their current job were also included.

Survey Results

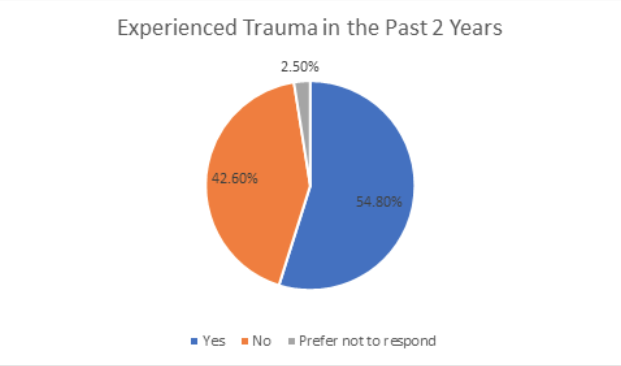

In the current study, more than half of survey respondents (54.80%) indicated they had experienced at least one traumatic event within the past two years. These findings indicate that during the past two years, employees have experienced significant traumatic events which have negatively impacted their well-being for a month or more. Compared to past research by Lee et al. (2020), this study found a higher percentage of employees reported trauma. There are two potential explanations for this finding:

1) The question to assess trauma in this study did not take an inventory of symptoms through a formal trauma assessment but instead asked respondents if they had experienced a negative event in the last two years that affected their well-being for more than a month;

2) Covid-19, civil unrest, and events highlighting racial disparities increased trauma experienced by employees in this study.

Most likely, it is a combination of how trauma was defined and classified in this study as well as increased experiences of trauma in the past two years.

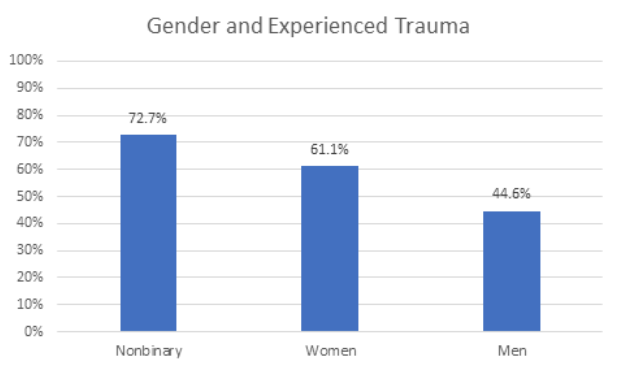

There was a stark difference in the rates of trauma when comparing genders. Trauma was reported most frequently among non-binary respondents with 72.7% of non-binary respondents reporting trauma within the past two years. It is worth noting that the non-binary sample size was small with only 13 respondents, however, this finding aligns with research that has found non-binary and transgender people are more likely to report victimization experiences compared to the general population (Rimes and colleagues, 2019). Women reported the next highest incidence of trauma with 61.6% of women reporting trauma. Previous research supports the higher rate of experienced and reported trauma among women (Farhood and colleagues, 2018). One potential explanation for this discrepancy is the nature of traumatic events that women more frequently encounter. Women are much more likely to experience trauma related to sexual assault (17.6%) vs (3.0%) than men. Typically, there is less positive social support for survivors of sexual assault compared to trauma from combat, which men experience more frequently than women (DeLong, 2012). According to the social causation model, people with less social support are more prone to post-traumatic stress disorder (Wang and colleagues, 2021). Men reported the lowest incidence of trauma with 44.6% experiencing a traumatic event in the past year.

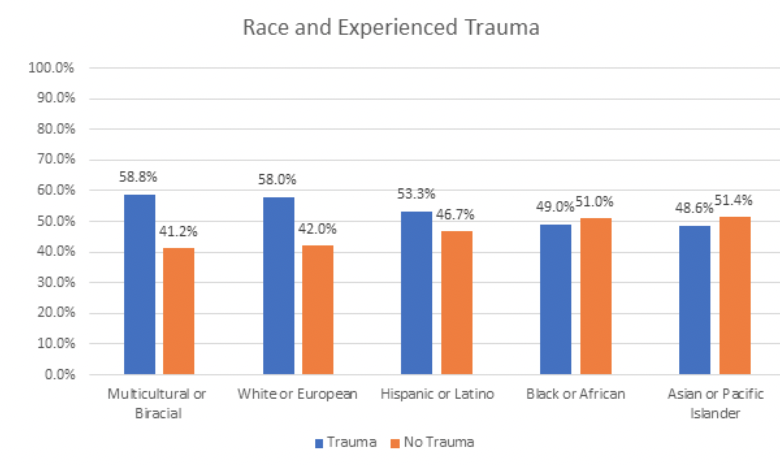

In terms of race, multicultural or biracial people reported a traumatic experience most frequently (58.8%) with White or European people close behind (58.0%). Hispanic or Latino people reported the third-highest percentage of experienced trauma (53.3%). Black or African people reported the fourth-highest percentage of experiencing trauma (49.0%) in the past two years followed by 48.6% of Asian or Pacific Islanders. These results are partially aligned with previous research findings that Asian or Pacific Islanders report the lowest rates of experienced trauma and Hispanic or Latino people report intermediate levels of trauma; however, the survey results counter research by Roberts and colleagues (2011), who found that Black respondents were most likely to experience PTSD.

The present survey found White or European as well as Multicultural or Biracial respondents reporting the highest percentage of trauma while Black or African people reported intermediate levels of trauma. There are two potential explanations for this difference:

1) Small sample sizes for Black or African participants (24 respondents) may not accurately represent the larger population;

2) Half the Black or African sample was from South Africa where trauma was reported at a lower rate of 42.3% than in the United States at 57.0%.

Overall, the literature examining race and PTSD is complex with many interacting variables including potentially traumatic event exposure, coping styles, social support, historical context, as well as the type of trauma exposure (Valentine and colleagues, 2019).

Sources of Trauma

Work vs Personal Trauma

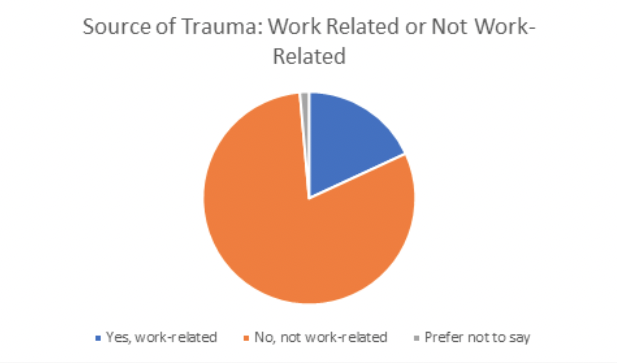

Recognizing the sources of trauma is important for preventing the occurrence of traumatic events as well as supporting employees after they have experienced traumatic events. Out of the 282 respondents indicating that they experienced trauma within the past two years, a strong majority (over 80%) indicated that the traumatic events that took place were not work-related.

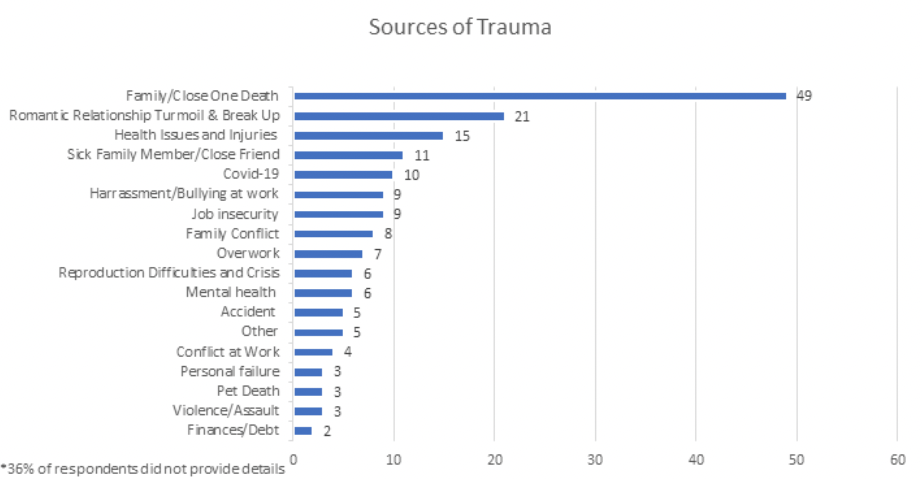

In response to an open-ended question asking about the source of the traumatic event, many employees 36% (99) elected to skip providing details about the traumatic event. However, the remaining 64% (176) included a brief explanation of the source of their traumatic experience. By far, the most frequently cited traumatic event 27.8% (49 of the 176 explanations) was the death of family members and close friends.

Effects of Trauma

The effects of experienced trauma are far-reaching and pervasive. Regardless of the source of trauma, those who have experienced a traumatic event show negative effects in both work and non-work life domains. As laid out in this research, trauma affects personal functioning, stress, happiness at work, well-being, work outcomes, and social relationships and connection.

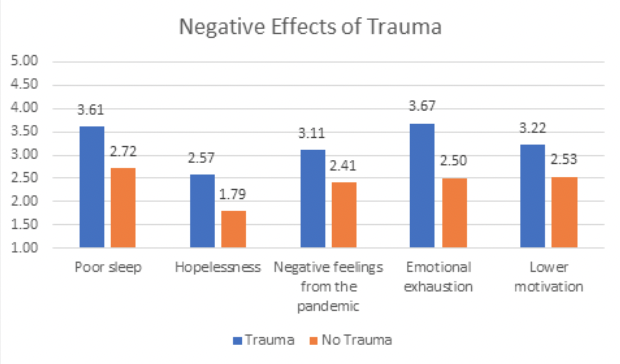

Overall trauma is related to negative effects on personal functioning. Specifically, respondents who reported experiencing trauma in the past two years also reported significantly more poor sleep, hopelessness, negative feelings from the pandemic, emotional exhaustion, and lower motivation. Taken as a whole, trauma can affect both physiological functioning (Liang, Hanig, Evans, Brown, & Lian, 2018) and self-worth (Vogel & Mitchell, 2017).

On top of the effects of direct trauma, employees can also experience vicarious trauma when hearing about or witnessing other’s traumatic events and engaging in empathetic responses (Kim and colleagues, 2021). Vicarious trauma is also tied to increased hopelessness from witnessing another person deteriorate and struggle with trauma (Ricciardelli and colleagues, 2018).

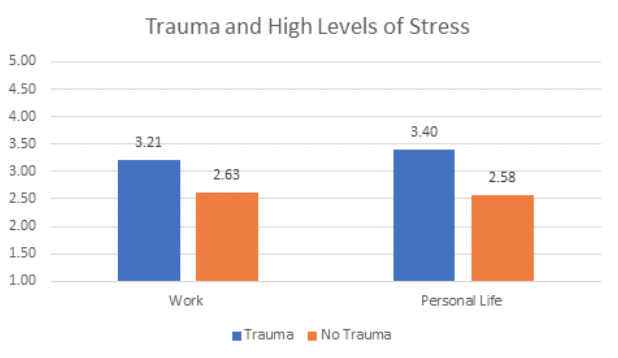

Not surprisingly, the effect of trauma within the past two years is also significantly tied to daily stress both personal and work-related. A strong correlational relationship between trauma and multiple types of stress was also discovered in a research study on emergency room nurses during Covid-19 (Vagni, and colleagues, 2020). Experiencing this additional stress can also cause people to feel ashamed of their stress reactions and subsequently withdraw from social relationships and support resources (Protocol, 2014). Over time, the experience of increased stress can inhibit the ability to heal after trauma.

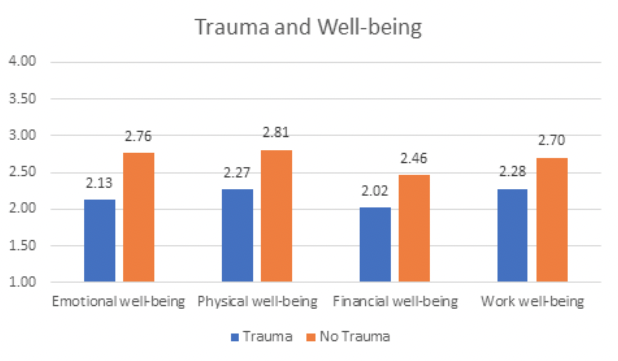

Trauma is also negatively related to 4 key domains of well-being: emotional, physical, financial, and work well-being. According to Kira and colleagues (2021), the connection between trauma and reduced well-being is explained by increased depression related to the trauma which subsequently impacts well-being. In a study of Public Safety Personnel, many of those affected by trauma also reported that their organization did not care about their well-being (Ricciardelli and colleagues, 2018). In the same study, many respondents also indicated physical side effects of trauma such as stomach aches and medical issues. Most notably in the current survey results, all four key areas of well-being were significantly lower for employees who experienced trauma in the past two years.

Employees who have experienced trauma are likely to struggle with maintaining appropriate work behavior because of long-term difficulties resulting from trauma (Thau & Mitchell, 2010). In a study of healthcare workers who experienced workplace violence, workers who experienced this specific trauma had more absenteeism, lower productivity, and more likelihood of turnover. The researchers concluded that traumatic workplace violence affects entire organizations and even whole communities. The current survey results showed workers who experienced trauma reported significantly more burnout. In addition, workers who experienced trauma also reported reduced engagement, barriers to performance, lack of progress toward goals, and lower organizational commitment compared to workers who had not experienced trauma. Ultimately, workers who had experienced trauma in the past two years were significantly more likely to quit their job.

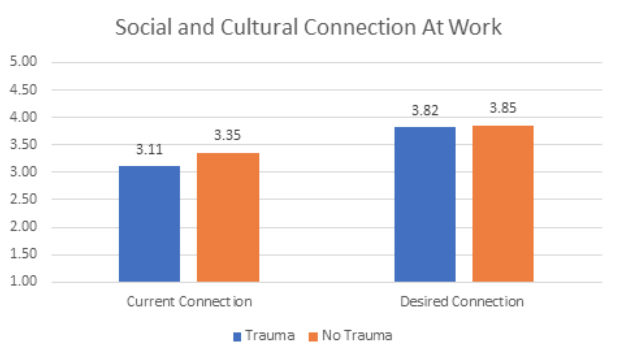

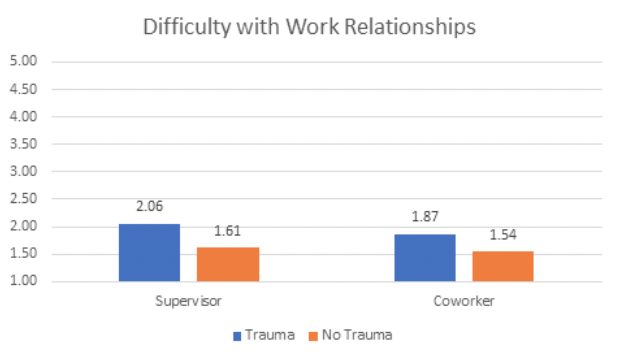

Trauma can heavily influence the way that employees interpret interactions at work. Employees who have experienced trauma in the past two years report less social and cultural connection at work as well as significantly more conflict with coworkers and supervisors. Social connection and positive interactions can serve as key supports for recovery after trauma; however, the very nature of trauma can be both isolating and conflict-inducing. On top of trauma interfering with potential social support, isolation and conflict can further increase trauma. Specifically, perceived interpersonal conflicts, particularly with supervisors, have the potential to cause re-traumatization of employees who are already suffering from trauma (Chan & McAllister, 2014). Therefore, social connection as a potential healer from trauma (Priesemuth and colleagues, 2014), maybe more challenging to attain because of the trauma itself.

Support for Employees Who Have Experienced Trauma

As discussed in the previous section, there are many persistent negative effects of trauma. According to the current study, more than half of employees experienced some form of trauma within the past two years, and the relationship between trauma and negative experiences was far-reaching and closely related to important work factors. Based on this sample, organizations and communities are strongly affected by the often-unseen trauma that employees experience in their personal and professional lives. Once exposed to trauma, the negative effects of trauma make it more difficult to heal from the initial traumatic event.

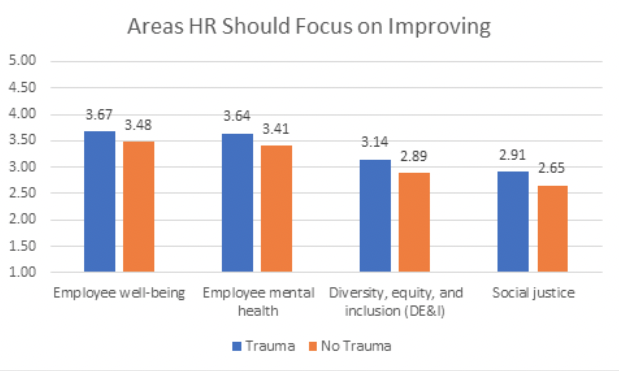

Employees who have experienced trauma have different needs compared to employees who have not experienced trauma. When comparing employees who had reported experiencing trauma vs employees who did not report experiencing trauma, there were significant differences in desired areas of focus for HR. The desire for well-being support, employee mental health, DEI, and social justice were rated as significantly more important for employees who experienced trauma.

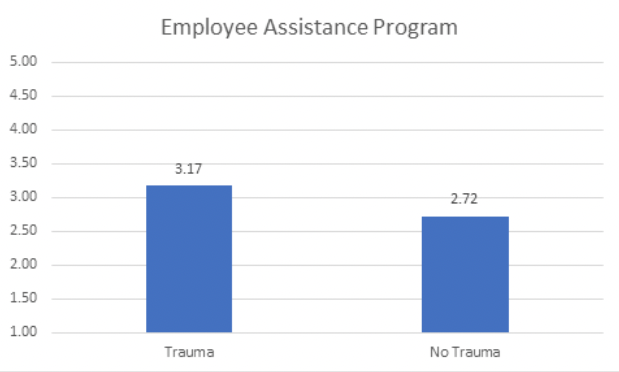

When asked about specific well-being support, employees who had experienced trauma in the last 2 years were significantly more interested in employee assistance programs. This is explained by the nature of employee assistance programs serving as important resources for employees facing major life changes and difficulties. In research examining the role of EAPs in supporting employees, recommendations include pre-exposure training, post-exposure support, consultation, and support staff as well as access to resources (Van Wyk, 2011).

Recommendation for Human Resources Professionals and Managers:

Research indicates that people who have experienced trauma can overcome their negative experiences if the right environment and support structures are in place (Covington, 2008; Najavits, 2002). In a recent study examining compassion satisfaction and stress in social workers, researchers found that organizational support through good leadership and feeling protected by the organization predicted lower work-related stress and subsequently, lower burnout (Senreich et al., 2020). According to SAMHSA, a trauma-informed workplace includes a thorough understanding of the widespread impact of trauma as well as the many paths to recovery after trauma. Along with this understanding, trauma-informed workplaces include education and knowledge on the effects of trauma which inform policies, procedures, and practices to create a safe environment.

8 Recommendations for Building a Trauma-Informed Workplace:

1) Values and Leadership

Incorporate empathy and supporting others into organizational values. These values will guide the other 8 recommendations. In practice, this involves leadership explicitly supporting a trauma-informed work culture while reinforcing those values through policies, communication, and action. Leaders should also promote a culture that does not allow behaviors such as abusive supervision, bullying, or sexual harassment which can be traumatizing or re-traumatizing.

2) Ensure resources are available

Resources should be available in multiple avenues and formats. For example, there should be self-serve options as well as guided options for getting support. According to our research, it’s important to offer an EAP that is trauma-informed and confidential. In addition, helping employees support good well-being and mental health habits through self-service trackers and apps. Frequently remind all employees of the available resources.

3) Training to promote understanding and awareness of trauma.

Training can help employees support others and cope better when faced with traumatic events. Basic trauma-informed training should include education about the prevalence of trauma, the impact, as well as trauma-informed strategies for working sensitively with trauma survivors. In addition to training employees, managers should get training on how to assist employees and others who have experienced trauma. This training would include strategies for avoiding triggers, knowledge of helpful resources, and strategies for offering support.

4) Inform policies, procedures, and practices to create a safe environment.

In practice, this involves supporting social justice and actions to build a strong DE&I work culture. Many sources of trauma are a direct result or related to a lack of social justice. In addition to a foundation of social justice and DE&I, organizations should work to incorporate trauma-informed policy. Policies that are trauma-informed account for the effects of trauma and involve listening to trauma survivors as well as anticipating potential triggers and solutions.

5) Physical environment

Examine the physical work environment to ensure that it promotes safe and equitable work. Specifically, check to make sure that the environment is equally accessible for people with disabilities and free from stimuli that may cause re-traumatization. For example, spaces that emphasize larger power differentials or include tight physical spaces can be retraumatizing for someone who has experienced abusive supervision or an accident where they were physically trapped, respectively. Ensure that there is space and privacy for self-care and well-being activities.

6) Communication

Organizational leaders should communicate both support and guidance for a trauma-informed workplace. Communication within the organization should also be trauma-informed. Specifically, it is important to recognize that when someone who has experienced trauma is experiencing high stress, communication becomes significantly more challenging. For this reason, conversations should be kept as low-stress as possible and employees should always feel safe asking to resume a conversation later if needed.

7) Survey and Interventions

Check-in with employees on their well-being as well as the need for support. These check-ins should be through different methods including direct conversations with managers as well as anonymous surveys to assess overall organizational well-being and trauma-support needs. Anonymous survey results should be shared with employees along with planned initiatives to address gaps in well-being and trauma support.

8) Evaluation and Refinement

Assess employee reactions to trauma-informed initiatives through surveys and direct conversations. Conduct an assessment before implementing trauma-informed initiatives to get a baseline measure of areas frequently affected by trauma: burnout, motivation, feeling of hopelessness, sleep, well-being, engagement, performance, commitment, turnover intentions, social connection, and working relationships. In addition to self-report, collect objective data on absences, turnover, performance, and any additional areas of importance. After implementation of trauma-informed workplace practices, assess areas from the pre-survey and assessment to determine the effects of the trauma-informed practices. Utilize employee survey feedback and recommendations to determine areas to improve.

Conclusion

Ultimately, it’s important to recognize that trauma is a common experience that can negatively affect employees, organizations, and communities. As a manager, HR leader, or worker, you can make a difference by promoting trauma-informed practices in your workplace.

About the author:

Elora Voyles, PhD: Dr. Elora Voyles is an Industrial-Organizational Psychologist and People Scientist with TINYpulse, a Limeade Company. She has a strong background in organizational consulting. Client organizations have ranged from small local businesses to Global Fortune 500 organizations. Dr. Voyles’ consulting expertise includes survey design, data analysis, employee engagement, and action planning.

Limeade Institute: The Limeade Institute was established in 2006 and delivers employee experience research to help you improve people and business results. Our team of Psychologists, Consultants, and Data Scientists focus on improving work experiences through research on topics such as well-being, psychological safety, reducing burnout, and employee mental health.

References:

Chan, MeowLan Evelyn, and Daniel J. McAllister. "Abusive supervision through the lens of employee state paranoia." Academy of Management Review 39.1 (2014): 44-66.

Covington, S. (2008) “Women and Addiction: A Trauma-Informed Approach.” Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, SARC Supplement 5, November 2008, 377-385.

DeLong, H. (2012). Social support in PTSD: An analysis of gender, race, and trauma type. Discussions, 8(2).

Farhood, L., Fares, S., & Hamady, C. (2018). PTSD and gender: could gender differences in war trauma types, symptom clusters and risk factors predict gender differences in PTSD prevalence?.Archives of women's mental health, 21(6), 725-733.

Kim, J., Chesworth, B., Franchino-Olsen, H., & Macy, R. J. (2021). A scoping review of vicarious trauma interventions for service providers working with people who have experienced traumatic events. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 1524838021991310.

Kira, I. A., Shuwiekh, H. A., Alhuwailah, A., Ashby, J. S., Sous Fahmy Sous, M., Baali, S. B. A., ... & Jamil, H. J. (2021). The effects of COVID-19 and collective identity trauma (intersectional discrimination) on social status and well-being. Traumatology, 27(1), 29.

Lee, W., Lee, Y. R., Yoon, J. H., Lee, H. J., & Kang, M. Y. (2020). Occupational post-traumatic stress disorder: an updated systematic review. BMC public health, 20(1), 1-12.

Liang, L. H., Hanig, S., Evans, R., Brown, D. J., & Lian, H. (2018). Why is your boss making you sick? A longitudinal investigation modeling time‐lagged relations between abusive supervision and employee physical health. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 39(9), 1050-1065.

Moll, S. E. (2014). The web of silence: a qualitative case study of early intervention and support for healthcare workers with mental ill-health. BMC public health, 14(1), 1-13.

Najavits, L.M. (2002). Seeking Safety: A Treatment Manual for PTSD and Substance Abuse. New York: Guilford Press.9Covington, S. (2008) “Women and Addiction: A Trauma-Informed Approach.” Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, SARC Supplement 5, November 2008, 377-385.

Priesemuth, M., Schminke, M., Ambrose, M. L., & Folger, R. (2014). Abusive supervision climate: A multiple-mediation model of its impact on group outcomes. Academy of Management Journal, 57(5), 1513-1534.

Protocol, A. T. I. (2014). Trauma-informed care in behavioral health services. Rockville, USA: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

Rimes, K. A., Goodship, N., Ussher, G., Baker, D., & West, E. (2019). Non-binary and binary transgender youth: Comparison of mental health, self-harm, suicidality, substance use and victimization experiences. International Journal of Transgenderism, 20(2-3), 230-240.

Ricciardelli, R., Carleton, R. N., Groll, D., & Cramm, H. (2018). Qualitatively unpacking Canadian public safety personnel experiences of trauma and their well-being. Canadian Journal of Criminology and Criminal Justice, 60(4), 566-577.

Roberts, A. L., Gilman, S. E., Breslau, J., Breslau, N., & Koenen, K. C. (2011). Race/ethnic differences in exposure to traumatic events, development of post-traumatic stress disorder, and treatment-seeking for post-traumatic stress disorder in the United States. Psychological medicine, 41(1), 71-83.

Senreich, E., Straussner, S. L. A., & Steen, J. (2020). The work experiences of social workers: Factors impacting compassion satisfaction and workplace stress. Journal of Social Service Research, 46(1), 93–109.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. SAMHSA’s Concept of Trauma and Guidenace for a Trauma-Informed Appoach. HHS Publication No. (SMA) 14-4884. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2014. https://ncsacw.samhsa.gov/userfiles/files/SAMHSA_Trauma.pdfaccessed December 11, 2020.

Thau, S., & Mitchell, M. S. (2010). Self-Gain or Self-Regulation Impairment? Tests of Competing Explanations of the Supervisor Abuse and Employee Deviance Relationship through Perceptions of Distributive Justice. Journal of Applied Psychology, 95, 1009-1031. https://doi.apa.org/doi/10.1037/a0020540

Vagni, M., Maiorano, T., Giostra, V., & Pajardi, D. (2020). Hardiness, stress and secondary trauma in Italian healthcare and emergency workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sustainability, 12(14), 5592.

Valentine, S. E., Marques, L., Wang, Y., Ahles, E. M., De Silva, L. D., & Alegría, M. (2019). Gender differences in exposure to potentially traumatic events and diagnosis of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) by racial and ethnic group. General hospital psychiatry, 61, 60-68.

Van Wyk, A. A. (2011). An Impact assessment of a critical incident on the psychosocial functioning and work performance of an employee. Pretoria: University of Pretoria. (MA Dissertation).

Vizheh, M., Qorbani, M., Arzaghi, S. M., Muhidin, S., Javanmard, Z., & Esmaeili, M. (2020). The mental health of healthcare workers in the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review. Journal of Diabetes & Metabolic Disorders, 19(2), 1967-1978.

Vogel, R. M., & Mitchell, M. S. (2017). The motivational effects of diminished self-esteem for employees who experience abusive supervision. Journal of Management, 43(7), 2218-2251.

Wang, Y., Chung, M. C., Wang, N., Yu, X., & Kenardy, J. (2021). Social support and posttraumatic stress disorder: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Clinical psychology review, 85, 101998.

Wang, C., Pan, R., Wan, X., Tan, Y., Xu, L., Ho, C. S., & Ho, R. C. (2020). Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general population in China. International journal of environmental research and public health, 17(5), 1729.

Share this

You May Also Like

These Related Stories

.png?width=534&height=632&name=blog%20ad%20(1).png)